As individuals, some of us tend to messy disorder while others keep the laundry quickly folded and the dishes stacked back in their places before day’s end. In spite of these personal styles, each of us belongs to a larger, and generally well ordered, social framework. These frameworks are as diverse as human languages and, like languages, many are composed of subsets of order that differ one to the next. This can sound abstract so it’s a delight to find three excellent books for middle grade kids (and the adults in their lives) that give the abstraction of social order concrete presentations. Together the three provide an international and even pan historical tour of how cultures organize themselves (and in many cases the cultures of other peoples). The illustrations provide depths of information and their brief texts point up avenues ready for middle grade readers (and older ones, too) to explore further. All are composed with input by experts in the fields of history, anthropology, and how to tell a compelling nonfiction narrative.

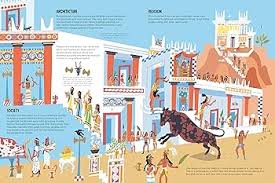

We’ll start with RISE AND FALL: GREAT EMPIRES THAT SHAPED THE WORLD written and illustrated by Peter Allen and published by Cicada Books. Before cycling through features of each of nine empires presented, this carefully researched and generously illustrated book describes the hallmarks of civilizations that have had lasting effect on generations to come—including, in some cases, our own. Empires have made impacts on every continent except Antarctica, yet each followed different types of leadership, of necessity worked with different landform and climate conditions, suppressed or vanquished cultures they considered competitors for dominance, in local lives, and supported some universal advancements of human development in diverse fields. Some empires lasted only a generation while others endured across centuries. Each rose to spread across a territory, developed a religion and/or other systems of control through belief, and experienced benefits of fine and/or applied arts and sciences. And each of the ones described here also met with decline due to varying counterforces, some natural (disease) and others political (an overwhelming force by outsiders). Because of the bite-sized nature of the information incorporated here, it is easy to flip back and forth to compare and contrast both similarities and differences, making this a welcome volume for exploring questions of how and why instead of being limited by traditional history teaching’s when and who (was the leader).

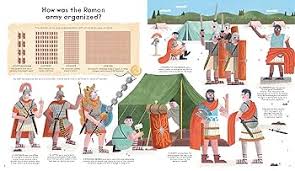

An empire that is probably familiar, in name if not in substantial detail, to even young readers that is not covered in RISE AND FALL steps forward in ROMAN SOLDIERS, written by Tegen Evans, illustrated by Tom Forese, and published by Nosy Crow as part of their “Picture History” series. Empires must subdue and absorb into their cultural influence peoples beyond their initial environmental area. The Roman Empire spread its influence and power into much of Europe and Britain as well, maintaining its predominance two thousand years ago. Rome’s highly regulated army had to cope with various climates, terrains, food and water access, and human needs at outposts far from the rulers. With resources from the British Museum, the author and illustrator of ROMAN SOLDIERS offer detail and organizational structures of that army’s daily life from colorful pennants to marching formation diagrams. The pages here are as busy as a Roman military camp and seem to touch all five of our senses instead of staying flat on the page.

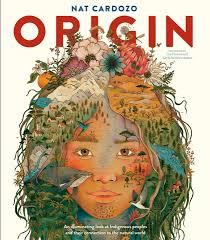

ORIGIN written and illustrated by Nat Cardozo, translated from Spanish by Ian Farnes and Layla Benitez-James, published by Red Comet Press, is not about empires at all, but about the indigenous people, again worldwide, who have managed, at least in part, to escape being absorbed culturally into any assertive empire. Each oversized page spread here features a brief essay about a still-living group that has been able to maintain (sometimes with now frighteningly few numbers of fewer than 10,000) their traditional, environmentally-tied ancient culture. A couple of these Indigenous groups have, indeed, lost members to the modern world of empire-building and acculturation, including members of the North American Cherokee and the Northern European Sámi. Across from each of these narrative descriptions, Cardozo presents an ethnographically informed and visually fantastic face that includes the elements of that Indigenous culture’s natural world: in one, this places a frosted mountain at the top of the scalp, while in others rivers and birds flow across nose and cheeks. However, cultural elements are incorporated in these portraits as well, including hair beads or facial tattoos, and biological details peek though as well, in eye and skin colors. A final map shows how these Indigenous groups are still spread across the globe, without regard to modern (post-empire) political borders.

A significant takeaway rising from these three books presenting facts in highly visual manners is the attention drawn to how patterns are created, maintained, and made identifiers of specific cultures. Each empire presented in RISE AND FALL is shown to have created discrete architectural patterns as well as decorative motifs. In ROMAN SOLDIERS, we see how math and functional design patterns work in the numbering and formations of soldier subsets, based on factors of ten, and the dispersal of troops across newly won borders. ORIGIN takes pattern display to even more highly revealing levels by enfolding the environmental and traditional details of a culture into representation of a single face.

Another shared property of all three books is how successfully the authors and illustrators have enlivened facts, which are documented in each title, with words and images that encourage readers to feel present with the details. These three books are alive and will evoke an interest in digging further—and farther.